Hijacking the cause of women

We should empower women. This statement used to be a profound one. Today, it is almost meaningless. Everyone seems to agree with it and have their own interpretation about what the phrase means. In March 2017, Saudi Arabia launched a much-touted Girls’ Council. It was all about empowering women and girls. All thirteen people present on the stage were men. A couple of months prior, Donald Trump signed a policy on “empowering” women to weaker reproductive rights, flanked by a dozen of his closest advisors, not a woman in sight.

The concept of empowerment has been hijacked, and not only by men. Female CEOs ensure us that there are no systemic problems around, and it’s all a matter of the woman just “leaning in” in conversations and being more assertive. Female TED speakers explain that it’s all a matter of finding and using your power pose and people will listen to you. In my everyday experience, in many organizations, women in leadership benefiting from the status quo are happy to equate women empowerment with their own empowerment. Some women in traditionally male but highly paid industries, say finance, are happy to be tokens of diversity.

So does empowering women have any meaning anymore? It does. It means changing the system which is the oldest pattern of social domination in existence. The researcher Valerie Hudson calls it the “patrilineal syndrome.” It is as old as society. Throughout much of history, women were objects. Killing and raping them meant little or no jail time. Paying them less than men, or not at all, was the norm. To this day, in some societies, women are being kept as slaves. And I don’t mean ISIS, I mean the West, where trafficked women are used as sexual objects. Between fifteen and thirty million women are living as forced labour as you read this.

Of the 87,000 women murdered in 2017, half were killed by an intimate partner or family member. More than one billion women lack any legal protection from domestic violence, one of the most pervasive forms of gender violence. During the COVID-19, domestic violence increased by up to 60% in some regions.

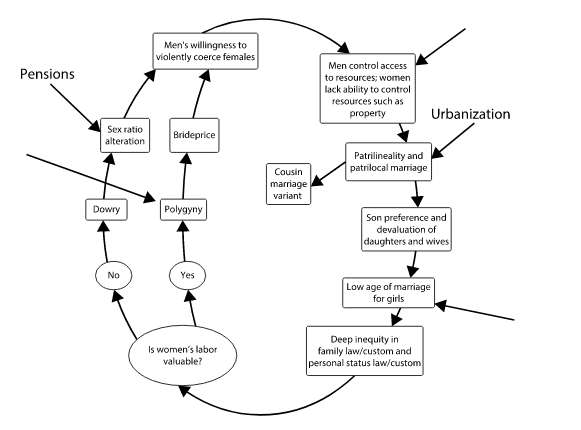

Women live in a world created by and for men. This system has its cycle of disempowerment with weak links that philanthropy can attack:

The patrilineal syndrome, with some of its weakest links pointed out through arrows. Adapted from Hudson et al, 2020.

Globally, there are three areas of investment in which philanthropy can produce the most benefit by exploiting these weak links.

Child Marriage

The first area of weakness in the syndrome is child marriage. The international public opinion has recently swayed decisively to the side of ending child marriage. The Elders, a group of respected elder statesmen and stateswomen, have launched the “Girls Not Brides” initiative. Even more impressively, since the turn of this century, fifty-two countries have increased their marriage age to eighteen years old or higher, and an additional eight countries have endeavored to close loopholes in their marriage laws that permit under-eighteen-year-olds to marry despite the fact that the stipulated age of marriage is eighteen. Some nations, such as Norway, refuse to recognize child marriages even if they were contracted in countries where the marriage was deemed legal.

Polygyny

Polygyny, the practice of having more than one wife, is another component that is vast in its import for the society and that is more susceptible to direct challenge than many of the other components. First, as research by McDermott and colleagues show in their survey of six countries where the practice is legal, “the majority of both men and women see little to no benefit from the practice and, in fact, are harmed by it.” Indeed, McDermott and her colleagues found less than 50 percent support among men for the practice in their survey. The harm, then, is not only to women. Most men in society will face a far more difficult marriage market as a result of the polygynous aspirations of the subset of elite men, and they are quite aware of this fact. In reality, it is only elite men, or aspirants to such status, who support the practice; this is a point of weakness in the patrilineal syndrome.

Property rights for women

Polygyny and child marriage are tightly wound up with women’s property rights – that is, both practices severely undercut those rights, and when they are curbed, women’s property rights significantly improve. Even so, the legal case for equality in property rights between men and women is even easier to make under current international and even national law than it is for child marriage and polygyny. As the global economic system has become more completely capitalist in nature following the end of the Cold War, the right of an individual to hold property and make contracts in their own name has been upheld across every continent.

The formal law of the land almost always upholds the property rights of all individuals, including women. International law also supports such rights for both men and women, the foundational case in point being the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights which explicitly states that the economic rights it enumerates belong to women as well as men. The problem is in the cultural practices that constrain the application of the law, practices such as patrilocal marriage, polygyny, and child marriage. Patrilineality does not countenance female control over valuable resources, for that would dilute the power of the male-bonded extended kin networks.

Men as crucial for the solution

As we have seen, the way to break the patrilineal syndrome is by targeting legislation and working with men, many of whom are not happy with the state of the affairs either. Women can only empower themselves in isolation so much.

This is a wake-up call for philanthropy, which is not particularly good in either domain. Investment in men’s groups by organized philanthropy is sorely lacking. In Switzerland, not a bastion of women’s rights but not a global backwater either, the few men’s organizations devoted to equality and equal sharing of household duties and childcare, constantly struggle for financing.

Only in 2020, against ferocious opposition from the corporate sector, Switzerland allowed fathers two weeks of paid paternity leave. Just for comparison, UNICEF suggests six months for both the man and the woman as the baseline. The burden of child-raising is then effectively still on the woman, as it is in most other countries. All this against the evidence that when men take paternity leave, women benefit – they end up returning to work more quickly, earning more, feeling better, and the sharing of household duties persists as a pattern for years. The patrilineal syndrome has different manifestations in different places. But it always works to disempower the women.

The backlash of men against women’s empowerment has been strong and real. The rise of far right parties across the world has been one of the results of men’s growing insecurities. When thousands of protesters took to the streets of Madrid in 2019 to commemorate the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, they were greeted with a demand from Spain’s surging far-right Vox party – that the country repeal a landmark law aimed at protecting women from violence, citing its “unfairness toward men.” The number of femicides (murdering women on account of their gender) in Turkey has nearly quadrupled between 2011 and 2018, according to an advocacy group, We Will Stop Femicides. Counties such as Russia and China are rolling back legislation that protects women to appeal to religious and conservative groups.

Men everywhere are insecure about the emerging woman, a woman who is educated and independent. For some of them, the threat is existential. Philanthropy Consultant , most of whom are male, need to help these men find a place in the new world. Otherwise, they will cling on to the old one, and defend it violently and till the end.